Historical Articles

Below is a series of articles written by parishioner Patricia Cook, and illustrated by Jean Atkinson, for the Parish magazine.

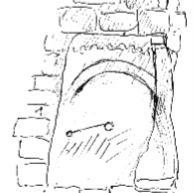

THE HOLY WATER STOUP

As you step inside St Mary’s Church look to the right. In the wall, occasionally holding flowers, is an unusual object in an Anglican church. This is a Holy Water Stoup. It was hidden from view for hundreds of years and only seen during the last few years.

Apart from St Mary’s, there are only four remaining stoups in Hertfordshire churches. Others are to be found throughout the country, usually inside the church itself, but sometimes in the south porch.

In medieval times the stoups held holy water, which was blessed once a week before mass. On entering the church, worshippers dipped their fingers into the water and crossed themselves as a reminder of their baptismal vows. To prepare the water, salt was exorcised, then blessed; the water itself was then exorcised and blessed, the salt was sprinkled over it in the form of a cross,and then a final blessing given to the mixture.

Holy water stoups are still in use in the Roman Catholic Church, and in many Anglo-Catholic churches. However, at the time of the Reformation in the 16th century, their use was discontinued in the Church of England, and many were destroyed, especially by the Puritans in the 17th century, along with many other church fixtures and fittings which were thought to be too reminiscent of Roman Catholicism.

At St Mary’s the front of the basin was removed, and the remainder filled in, plastered over and whitewashed. During the restoration of the church in 1991-2 the stoup was discovered and opened up. There was some discussion as to whether it should be left in the state in which it was found. But a new basin was made and attached to the existing remains, and now flowers are displayed there from time to time. As you can see, the shape of the arch, called an ogee, is very similar to the design of the top of the windows, suggesting it was made at the same time, probably around 1341.

SEATING OVER THE YEARS

When St Mary’s was re-ordered recently several people lamented the loss of the choir stalls and other pews removed at this time. It appears that a few people believed they were medieval.

However, all the pews in the church are Victorian, dating from 19th century restorations. The large box pew belonging to Potterells, situated almost exactly where the re-positioned choir now sits was retained, as was a smaller box pew in the chancel for North Mymms House.

If you look at the framed drawing dated 1859 on the north east wall, above the candle stand, you will see, with some difficulty, the seating arrangement which was used. Apparently there were so many objections to the re-pewing that the archdeacon was called in! **

It is interesting to see that the large houses in the parish each had their own family pew near the front, with servants graded by seniority at the back. At a later restoration, in 1871, the box pews were removed and the choir stalls built.

In medieval times there was practically no seating in the church, only perhaps a stone ledge running round the wall for the lame and elderly. This led to the phrase ‘the weakest go to the wall’. The congregation either stood or possibly knelt, a practice still evident in Orthodox churches today.

Some of the medieval pews were beautifully carved, with ‘poppy-heads’, and animals and even scenes from the Bible. Animals and even mermaids were quite commonly seen. Our pew-ends have simple leaf decorations. If you look carefully you will notice variations.

After the Reformation the sermon became the most important part of the service, often lasting up to one hour, and seating was needed, first benches, and later backs to these .Then came the large box pews, some of which even had fireplaces! Rents were usually paid for these, a custom which has only recently disappeared.

Lately the need for pews has diminished. Services now take different forms, with the congregation moving about more. Also, flexibility is now important, and many churches have removed most or even all of their pews and introduced stacking chairs to allow for greater space for church events.

THE DECALOGUE BOARD

You can see one in St Mary’s, high up on the east wall of the chancel. The Decalogue (a word derived from the Greek) is the term for the Ten Commandments. The Decalogue Board is a large board upon which the Commandments are written. These became a regular part of church furnishings in the reign of Elizabeth I, when it was state policy to clear churches of the decorations and adornments, which were regarded as 'popish’.

Medieval churches had a rood screen, that is a screen between the chancel and the nave. There was a beam, or rood, on which were statues of Jesus Christ in the centre, with the Virgin Mary and St John on either side. Sometimes there was a rood loft, from which the gospel and epistle were read. Nearly all of these were removed after the Reformation, though in some parts of the country they may still be found, as can a few modern versions. Blocked up doors are often visible in old churches.

In 1560 Elizabeth ordered Archbishop Parker to see ‘that the tables of the Commandments be comely set or hung up in the east end of the chancel’. The Creed and Lord’s Prayer were not necessarily required to be displayed, but were felt to be ‘very fit companions’ for the Commandments. Decalogues were also set up on the tympanum - panelling which filled the curve of the chancel arch to replace the discarded roof loft.

In most churches today, the Decalogue boards have long since been removed from their position behind the altar and are usually displayed on a convenient wall of the nave or aisles. In St Mary’s the Commandments, the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer are visible in the chancel, having been cleaned a few years ago.

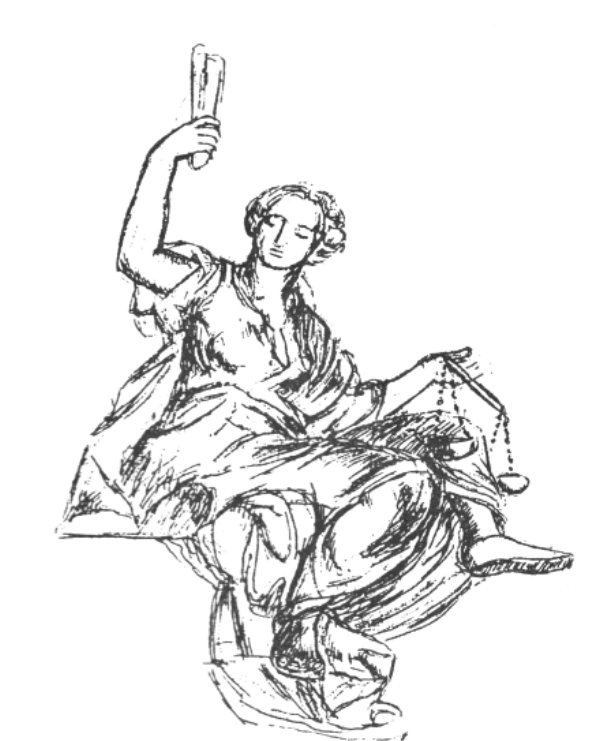

THE SOMERS MEMORIAL

St Mary’s has a number of fine memorials of which three are rather special. The 14th century brass of William de Kestevene, the 16th century alabaster Beresford tomb, and the 18th century marble of Lord Somers. Many churches have doors to the vestry in the chancel, but not many have a door like that at St Mary’s!

When the NADFAS church recorders were doing their survey of the church, they were astonished to find that the door was part of a memorial to John, Lord Somers. He was an interesting character who, after an illustrious career during which he was one of the men who invited William III to assume the crown, fell into disgrace in 1700 because he was involved in the affairs of the pirate Captain Kidd, and ended his days in obscurity at Brookmans.

The monument, by the famous sculptor Paul Scheemakers, is of white, grey and black marble, and reaches to roof level. The door to the vestry is of white marble. Lord Somers was Lord High Chancellor of England, and the figure of Justice, wearing classical draperies and sandals, sits on a black sarcophagus, with a grey obelisk behind. This arrangement of classical figures was very popular in the early 18th century.

(Important Tudor memorials had a figure of the deceased, his wife and his family, with a row of children, boys on one side, girls on the other, often brightly coloured. The tomb of Robert Cecil, (who died in 1611), in St Etheldreda’s church in Hatfield, has a life-size figure of the earl, and underneath a skeleton, showing that however powerful one was on earth, in death all were the same.)

On looking around the church one can see the great changes in memorial sculpture. The earliest are the medieval brasses, originally on the floor, now on the chancel walls, the latest the 21st century memorial to Sir George Burns near the entrance.

Medieval and Tudor memorials usually depicted an image of the dead person, and were on the floor or in recesses. By the 18th century memorials were attached to the wall, and there are many of these in St Mary’s. Made of marble and stone, some have busts of the deceased, but most are quite flat and rather plain having only epitaphs recalling the apparently perfect life of the deceased. Children are amused by the wording on the memorial of the tutor to the Duke of Leeds’ children who apparently ‘expired without a groan’.

By the 20th century memorials took the form of flat marble plaques attached to the wall, no figures, but often with coats-of arms. The memorial to Sir George Burns is a fine example of modern craftsmanship as are the smaller plaques on the North wall. There are also a number of brass plaques - a medium popular from the late 19th century. By this date inscriptions usually have only biographical details and dates.

THE PULPIT

The pulpit at St Mary’s probably dates from the time of Queen Elizabeth I, although it is a Victorian reconstruction.

The side panels are Elizabethan or Jacobean, and may have originally been used as wall panelling. The patterns popular at that time were often copied from pattern books from Holland or Flanders.

The rose was a popular motif in Tudor times, the Tudor rose being a combination of the white rose of York, and the red of Lancaster. The strapwork shown was often used in decoration, and can also be seen at Hatfield House. The base is Victorian.

In the Middle Ages the Mass was celebrated behind a screen, and there was no seating in the nave. (The Orthodox Churches still follow this format). Some churches had stone benches at the foot of the walls, hence the expression ‘the weakest go to the wall’. Sermons were rare. Few medieval churches had pulpits, and those that did were mostly built of stone and of a wine-glass shape, sometimes with painted panels depicting the four evangelists.

After the Reformation there was much greater emphasis on communication between the priest and the people, and preaching became more important. Many pulpits had a ‘sounding board'or tester above to amplify the vicar’s voice.

By the 18th century pulpits were often two-or three-decker, with seating for the parish clerk on the lower part and perhaps another tier with a reading desk incorporated as well. Sermons could be very long, and some pulpits had an hourglass attached to remind the priest (and possibly the congregation!) of the time.

In some churches the pulpit was moved to the nave and seating rearranged. In Great St Mary’s Church in Cambridge the pulpit is movable, swinging from the side of the nave to the centre as required!

Some of the 17th century churches have a very grand stair up to the dominant pulpit, as is the case in many non-conformist churches. By the 19th century the priest was conducting the service from the chancel, and pulpits were simplified, although some of the earlier ones remain.

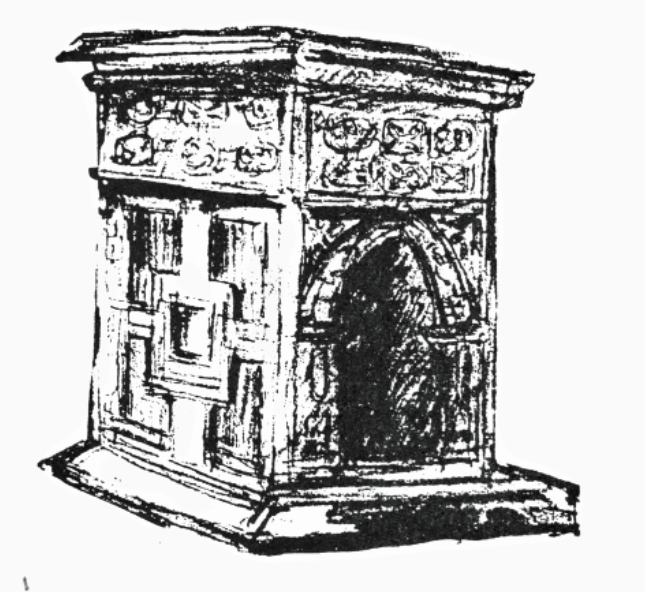

A RARE TOMB

One of the most interesting tombs in St. Mary's is that of the Barforde or Beresford family, below the northwest aisle window.

Made of Derbyshire alabaster (a sort of gypsum resembling marble) with the figure carved and the lines of the carving filled with bitumen. This is an extremely rare form of tomb, although there is one dated 1549 at Cleshill in Warwickshire. The delicately carved figure wears a Spanish farthingale, a popular fashion of the 16th century.

This tomb was originally against the south wall of the chancel, but during the restoration of 1871 when the choir pews were installed it was removed.

Unfortunately , in order to fit into its present position the tomb appears to have been partially destroyed, the back and part of the sides removed, and the top slab fractured. There is a raised inscription running right round the edge of this slab, but the lettering is illegible. The arms on the side of the tomb are those of the Beresford family, collared and chained bears.

It is not known who is represented on this tomb. The family lived in North Mymms in the 16th century, and two sisters, Elizabeth and Mary died within three months of each other in about 1584, so possibly this is a memorial to both of them.

There is another fascinating contemporary tomb in St Catherine's chapel, almost hidden by the organ. Only the end is visible. This is probably the tomb of Elizabeth Frowick who married Ralph Coningsby, and whose grandson built North Mymms House. The stained glass in the chapel has the arms of the Coningsby family.

The fact that these tombs were placed in the church signifies the importance of these families, who were local landlords and benefactors to the parish.

THE KESTEVEN BRASS

St Mary’s has a number of memorial brasses which can now be found mounted on the walls.

Of these the earliest and the most important is that of William of Kesteven, which is found on the north wall of the chancel. William was the incumbent, or vicar, from 1344 until his death in 1361, having held land in the parish as early as 1337.

There was originally some doubt as to whether the figure was that of another early incumbent, Thomas de Horton, but in 1949 the shield of arms below the figure was confirmed to be that of William de Kesteven.

He is shown in Eucharistic vestments, with chalice and paten, under a canopy, with figures of Christ, saints and angels in panels above it, and his shield of arms below, and various saints on the sides. Christ is holding the representative of the soul of William on his lap. The brass is worth a close look, as it is beautifully worked. The swirl of the small figures is typical of 14th century art.

The workmanship is Flemish, and similar to that of Abbot de la Mare, the Abbot of St Albans, which can be seen in the Cathedral. The metal used is latten, an alloy of zinc and copper, and it would have been set in stone on the church floor, or on a tomb chest. In many churches the brasses have been reset and placed on the wall to avoid further wear and tear. Sometimes the stone has been left in place.

Brass memorials were popular between 1250 and 1650, and about 8,000 remain in England, more than in any other country, although far more have been lost for various reasons. Occasionally a brass was reused, the back being engraved with a different image. This is known as a ‘palimpsest’.

On such memorials heraldic devices and Christian symbols were often featured. In the 14th century most were clerical figures, but later smaller brasses, often in memory of whole families, became popular. Examples of these can be seen on the south wall of the chancel, one of which depicts Robert Knolles and his family.

THE MASS DIAL

As you walk towards the church, have you ever looked high up at the corner of the church near a large tomb? You may not have noticed what appears to be a rather damaged corner stone. If you look carefully you can make out what appears to be a circular incision at the top of this stone. This is a Mass Dial, and was used before the Reformation to mark the time of the mass and other services. These are to be found near the church entrance for obvious reasons, on or near the south door, and are usually a complete circle. Some of the dials date from Saxon times and these can still be seen on many churches. Many are only a few scratches.

Circles are usually about six inches in diameter, with lines radiating from a central hole. A wooden or metal peg, called a gnomon, was put in the hole, and its shadow marked the time of day; a primitive sundial, but one with a specific purpose. There were marks which gave the times for morning mass, noon and vespers (evensong) to make sure that both the priest and people were in time for services in the days before clocks and watches. Occasionally, the line for mass is thicker, or identified by a short crossbar.

The dial at St Mary’s has a double circle, above which is an inscription. It is very difficult to read this, as it is badly weathered. It consists of some signs under a curved line, below which is a line of letters. The date is 1584, well into the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. The lower part of the circle is missing, but at about ‘eight o’clock’ there appear to be numbers.

In the 17th century churchyard crosses had to be reduced in size, and many of the stumps had a horizontal plate put on the top, and were used as sundials. Later, in the 18th century, most churches were given clocks, which are usually high up on the tower, in order to be visible from a distance.

GARGOYLES, CORBELS OR LABEL-STOPS?

What is the difference? Well, gargoyles are usually outside of the church, acting as waterspouts, particularly where there is a parapet, while corbels and label-stops can be either outside or inside. What they have in common is that they often take the form of human heads, some very odd indeed. (Just to confuse the issue, some people call corbels gargoyles!)

Medieval gargoyles were often made by itinerant masons who were free from restraint, and were allowed to let their imagination run riot, and not always in the best of taste!

Corbels are either single, supporting a beam, or a corbel-table, that is, a row of corbels running along a cornice usually outside just under the roof. In some churches a corbel-table can be seen inside. Label-stops, however, are at the end of a 'label' or 'dripstone', which is a surround to a window, or framing the arcade of the aisle or nave. If on the exterior, a dripstone served to carry away water from the window tracery.

At St. Mary's we have none of these outside, apart from what appears to be Victorian gargoyles high up on the tower. These seem to be only decorative and fulfil no useful purpose, being too low to be waterspouts.

Inside, there are both corbels and label-stops. The corbels are high up, most supporting the roof, although at the west end, two appear to support nothing at all. These may indicate an earlier roof than the present one. Some of the corbels could possibly be later, having been put in when the roof was renewed. The label-stops, or head-stops, to introduce yet another name, are lower down, in the nave arcade.

Some of the figures are almost regal, with head-dresses and clothing dating from the early 14th century, the time of the building of the church, while others are earthier, even with tongues out and pulling faces. It is sometimes said that local faces were used as models. If you look carefully, you can make out animal and foliage carving on other corbels.

ELEPHANTS & ROYAL ARMS

At the east end of the south wall of the chancel is a most unusual memorial. It is made of slate, and commemorates a member of the Fountaine family, who lived in the house known as Brookmans. This was destroyed by fire, leaving only the stable block which is now the clubhouse at Brookmans Park Golf Club. Slate is a fairly uncommon material to be used for memorials.

One can see three ‘elephants’, or at least what the designer thought they looked like! The idea of an elephant as a Christian symbol may not be immediately recognised, and why it should be featured in a 17th century English parish church is puzzling. The elephant is found in heraldry, symbolising strength and wisdom. Some animals are thought to have significance in the Christian Church. Obviously, the snake is seen as sinful, and the fox as wily and deceitful. It is often shown as preaching, in bench-ends and misericords. The lion is usually thought to be noble, but can also be wicked.

The rather sad epitaph to Theophila Fountaine, ‘dyed March 19th Anno 167½ aged six months’, reminds us how short the lives of many children were in the past. The recorded date may puzzle you, as it appears to be uncertain. This is because it is an example of the ‘old style’ of dating. Until 1752 the legal New Year in England began on March 25th, Lady Day, although New Year’s Day was reckoned as January 1st. Therefore it was customary to show both years for dates between January 1st and March 24th. Oddly, only the infant Theophila is commemorated here, as there is no mention as to where the rest of the family is buried.

The motto of the Fountaine family, VIX EA NOSTRA is, strangely enough, the same as that of Fulke Greville, who died in 1952, and whose memorial may be seen on the north wall of the nave.

ROYAL ARMS

The Royal Arms began to be displayed after the Reformation, showing allegiance to the Crown and not to the Pope. This became compulsory after the restoration of Charles II, as a pledge of loyalty to the king after the Commonwealth, during which many Royal Arms were defaced or hidden.

Most are painted on wooden boards, but some are carved wood or even metal. Often the initials of the monarch, and occasionally the date, are included in the design, and, particularly in the Stewart period, they also may carry loyal texts.

The coat-of-arms at St Mary’s is that of George III, who reigned from 1760 - 1820. Until recently it was displayed on the front of the gallery, but moved to the east end of the north aisle at the time of the recent re-ordering.

The arms displayed show those of the Hanoverian period, with the shield of Hanover together with that of Great Britain. This dates it to between 17141801. The fleur-de-lis of France is still displayed in one quarter, with the Hanoverian arms in another.

It is interesting to note that the French fleur-de-lis occupies a whole quarter, as does the harp of Ireland, leaving only the fourth quarter in which to squash the three lions of England, and the lion rampant of Scotland.

After 1801 the fleur-de-lis at last disappeared, and the Hanoverian arms were superimposed in the centre. The English Arms now occupied the first and third quarters, the Scottish the second, and the Irish harp the third.

On the accession of Queen Victoria the Hanoverian arms were dropped, as the Salic Law forbade the accession of a woman to the throne of Hanover. Supporters at the sides are the Lion and the Unicorn, representing England and Scotland. In the Tudor period, before the Union of the Crowns, the supporters were the Lion and the Welsh Dragon.

THE AMBER TANKARD

The most valuable item belonging to St. Mary's is the Amber Tankard, of German workmanship, dated 1659, which is now in the care of the British Museum (currently on display in Room 46)..

This was given to the church by Dame Lydia Mews, tenant of North Mymms House, the daughter of George Jarvis. Monuments to George Jarvis and his daughter can be seen on the north wall of the church building.

For more about the Amber Tankard see chapter 5 of Dorothy Colville's North Mymms - Parish and People

"Made in Nuremberg in 1659, its eight panels of amber are set in straps of silver gilt. The panels are carved in low relief with figures symbolic of the virtues, lively animals decorate rim and base, and St. George and the dragon appear on the lid.

Only one other tankard of nearly like design and workmanship is known to exist, and that has the vices where the North Mymms tankard has the virtues.

The Rev. G. Staunton Batty, vicar from 1880 until 1911, left a description of the figures carved on the amber panels: (1) Industry with distaff, (2) Faith with cross and chalice, (3) Fortitude with column, (4) Justice with sword and scales, (5) Charity with children, (6) Hope with anchor, (7) Temperance with ewer and goblet, (8) Innocence with book and lamb."

There is also mention of the tankard in chapter 6 of The Victoria History of Hertfordshire, edited by W. Page in 1908, as well as many other interesting facts about the fabric of the church.